Additional Contributors: Aurélia Azéma, Ann Boulton, Joachim Kreutner, Andrew Lacey, Susan La Niece, Mathilde Mechling, Dominique Robcis

Not all sculptures are in one piece. Some are intentionally cast in sections, and these parts are considered “primary castings” (as opposed to subsequent cast-on additions such as decorative elements, repairs, and reworkings, here called “secondary castings”). Casting in parts may reflect a particular ’s know-how as well as the limitations of local technology of the period and/or place. It may be done because it is easier, more efficient, or necessary to cast a complex or large work in smaller sections (see notably Case Study 7§4). Smaller elements allow for easier and limit difficult geometries that may impede metal flow or trap air (see GI§2.7), and they do not require the manipulation of large quantities of molten metal.

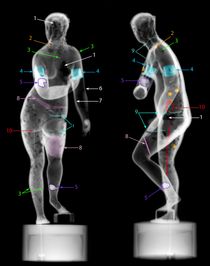

Casting in parts may also pertain to specific workshop or workflow organization.1 In some instances, parts that did not cast correctly need to be remade. The number of separately cast sections, their position, and the sequence in which they were put together is sometimes synthesized visually by researchers in the form of a .

Regardless of why a bronze was cast in separate sections, the parts can be joined in a variety of ways. This chapter provides examples of the different types of joining methods, how to recognize them, and the visual and analytical techniques that assist in their characterization.

1 What types of assembly features might be encountered?

Joining methods used to assemble bronzes fall into two basic categories: metallurgical and mechanical, both of which encompass a variety of different methods (fig. 201). That said, a single joint may itself combine metallurgical and mechanical components.

1.1 Metallurgical joining: fusion welding, flow fusion

welding, interlock casting, brazing, soldering

All processes in bronze sculpture have in common the use of liquefied metal.

1.1.1 Welding: Fusion welding and flow fusion welding

“” in modern metallurgy refers strictly to joining metal parts by creating atomic bonds. This can be done in two ways: with relatively low temperatures by forging (as is done by blacksmiths with iron, but is not used for bronze sculpture), or by partially melting the metal parts, a process referred to as fusion welding. Most forms of fusion welding used for bronze sculpture include the addition of a welding metal of a copper alloy more or less similar to that of the primary cast. High temperatures are required to achieve the melting temperature—typically above 1000°C for copper alloys. As the metals begin to melt, the parts can be joined by very careful temperature control before they become fully molten or start to lose their shape. The degree of metallurgical fusion and the strength of the joint depend on both the heat achieved during the process and the two alloys involved, namely the primary casting and the welding metal.

The methods used to melt the metal that is to be

joined have changed over time. To join the separately

cast parts of large bronzes during classical

antiquity, a quantity of bronze was melted separately

and poured along the joint until it melted the edges

of the adjacent primary cast parts while filling the

void between them. It acts both as a filler metal and

as the main source of heat (see

fig. 202,

video 12

Open viewer,

Case Study 1). This process, known as flow fusion welding, is

specific to ancient large bronzes and was used

systematically in their production. None of these

statues was cast in a single

.2

So far, the only known use of this process in

subsequent periods is in connection with repairs

during the Renaissance in Europe.3

Careful control of heat is essential in fusion welding

because the melting temperature of the repair metal is

close to that of the cast surface. Beginning in the

late nineteenth century, electric arc welding made it

possible to create a pinpointed concentration of heat.

In the early twentieth century, the blowtorch led to

the widespread use of fusion welding.4

Common types of modern welding equipment include TIG

(tungsten inert gas) and MIG (metal inert gas) (see

Case Study 7).

If the alloy of the joint (secondary casting) varies from that of the primary casting, differential may develop, thereby making the joint visible—perhaps even stand out—on the surface of a bronze (figs. 59, 203). Ancient Greek and Roman flow fusion welds often show up as a chain of oval shapes of varied color (corresponding to basins for increasing the contact area and for accumulating heat), possibly ringed by metal with a higher concentration of , that are easily recognized by the naked eye (figs. 204, 205).5

In both the TIG and MIG processes, the molten welding metal builds up at the joint. Unlike or , in which the majority of the added metal wicks into the joint, fusion welding results in a considerable amount of excess metal on both the internal and the external surfaces. For aesthetic reasons, the metal is usually ground or filed away from the outside, but often remains visible on the inside of the sculpture (fig. 59, see I.5§2.1 below).

Risks of misidentification/misinterpretation

Because both welding and brazing metals are copper based (see next section), it may be difficult to distinguish between the two by visual observation alone, thus requiring specific analytical techniques, including metallography and nondestructive testing techniques (see I.5§2.2 below).

1.1.2 Soldering and brazing

In both soldering and brazing, a metal with a lower melting temperature than the primary cast is added to the joint, aided by a flux that prevents oxidation, which could interfere with the bond. The metal of the pieces to be joined by soldering and brazing do not reach temperatures high enough to melt them (unlike with welding), and the resulting joints are therefore usually weaker (see also I.4§1.2.2). Solder or brazing metal may be added to a variety of joint types (fig. 201 D, E, F, G).

Both brazing and soldering may appear as straight lines of a slightly different color than the assembled pieces (figs. 188, 203). As a rule of thumb, soldering metals are white (silver or lead with added tin, bismuth, or other components) and typically operated at lower temperature (below 450°C), whereas brazing metal is yellow (copper alloys) and operated above 450°C, but such color distinctions may be difficult to discern visually due to and/or corrosion, and brazed joints may be hidden by . Any traces of flux left on the surface will eventually cause corrosion along the joint line (fig. 188).

Brazing and soldering have been used in a variety of periods and areas, including different parts of Asia (fig. 206) and modern Europe.6 As the brazing or soldering metal is of a different alloy than that of the surrounding parts, it may be revealed over time through corrosion.

Risks of misidentification/misinterpretation

Corrosion, patina, and may make it difficult to see a joint, which would be a different color. Later repairs may also complicate the identification of original soldering and brazing (see I.5§2.3 below and I.4§1.2.2). Radiography often remains the best way to identify the techniques used, and may even give an indication of the materials (figs. 187, 206).

1.1.3 Interlock casting or lock-on casting

In interlock casting, the temperature does not get high enough to produce a metallurgical joint. The poured-in metal may fill the gap between the joined pieces (fig. 201 F) and may also fill holes along the edges of the sections to be joined, ultimately acting as a kind of “staple” (fig. 201 G). Any metal can be used, including molten brazing or soldering metal. In a similar process, lap joints may also be secured by pouring in molten metal (fig. 201 I, J, see I.5§1.2.1 below). Interlock casting is found on many a bronze from Renaissance Italy (figs. 100, 207), as fusion welding was not practiced at the time, and also in a variety of other contexts.

Interlock casting appears as a combination of features, including a more or less continuous and thick joint area, which may be filled with brazing or soldering metal or surrounded by -like forms.

Risks of misidentification/misinterpretation

A rhythmic pattern of patch-like features in a concentrated area may pertain to any number of things (for instance hole or fills) rather than joints (fig. 119).

1.1.4 Casting on parts

Casting on parts is a particular type of interlock casting that refers to the joining of two parts by casting one element onto another, preexisting cast section. An entire section, such as an arm, may be cast onto a precast unit (primary casting). This can be used on large bronze sculptural objects to add parts (figs. 208, 209) as well as on smaller objects. Usually, this does not result in a fusion weld. Casting onto existing tangs or projections on the primary casting, as seen notably in ancient Chinese and Cambodian bronzes, helps strengthen the assembly.7 And casting on a part may also constitute a repair (see I.4§1.2.1).

Because the cast-on section will tend to shrink during cooling, a gap between the sections will often remain visible unless the joint area is reworked by hammering. Radiography is often necessary in order to identify a cast-on piece, whether it is an original assembly or a repair.

Risks of misidentification/misinterpretation

It may be difficult to distinguish cast-on parts from additions made in the wax (see I.5§2.1 below).

1.2 Mechanical joining

Mechanical joining can be achieved in a number of ways. One of the benefits (and potential weaknesses) is that some mechanical joining processes also allow for disassembly of the object.8 This was, for instance in early modern and modern Europe, key for that were cast in parts and assembled with removable rivets so that the sections could be separated for molding as needed (fig. 210).

1.2.1 Lap joints

Greater strength can be achieved by overlapping the two edges of a joint. Once overlapped, any number of methods may be used to secure the joint, such as solder, brazing metal, or inserted pins or rivets (fig. 201 I, J, K).

A sleeve joint is a specific type of lap joint in which a recessed sleeve is integrally cast onto one section (the male part) that is designed to slide inside the section to which it is affixed (the female part) (fig. 201 K). The attachment may be secured by one or more pins or rivets. This joining technique is common in a variety of cultures (fig. 65 point 4, figs. 127, 211, 212); it is often referred to as comprising mortise and tenon joints in the study of Southeast Asian bronzes and by scholars of European bronze sculpture. Instead of (or in addition to) pins or rivets, molten metal may be poured into the joint to secure the parts.

Without strong lighting, a perfectly designed sleeve joint may be nearly invisible on the exterior of the bronze when the outer contours of both sections meet in a narrow line and the pins are filed flush. The best designs often conceal even these very fine joint lines beneath clothing, drapery, or other design elements, making them very difficult to detect without radiography (figs. 212, 213) or access to the interior.

Risks of misidentification/misinterpretation

Repair that are in the area of a joint may be misidentified as pins used to secure the latter. Joints in which the two edges are flush with one another (for instance sleeve joints, interlock casting, and end-to-end joints) may be difficult to distinguish from one another (fig. 201).

1.2.2 End-to-end joints (butt joints)

As the name suggests, end-to-end joints butt up to each other without overlapping (fig. 201 D, H). They may be strengthened with some form of mechanical interlocking (such as rivets, fig. 201 H) and/or reinforced across the back or on the inner hidden surface with a layer of melted metal. Without such additional reinforcement, end-to-end joints are intrinsically weak, and with the exception of butt welding, they are most of the time mechanically reinforced.

Risks of misidentification/misinterpretation

From the outer surface, end-to-end joints look very similar to interlock casting joints.

1.2.3 Tangs and other extensions

A tang is an extension cast integrally with the figure and used to attach parts, mainly but not exclusively to mount a figure to its base (figs. 214, 215). A tang may be solid (for instance an integrally cast sprue extending from the foot of a figure) or hollow. The attachment process may simply consist of slotting the tang into a prepared hole in the base or feature to be added. In the case of a base, it may be left loose to allow it to be separated easily, or hammered down and splayed to lock it in place (fig. 216). Or one or more tapered pins, rivets, or screws may be used to hold the two pieces together (fig. 217).

We recommend that the term “tang” be used for sleeve joints that secure a separately cast element to a base (figs. 217, 218). Another variation common with in France is the use of threaded rods cast integrally with the figure and secured with nuts (fig. 219, see also Case Study 6).9 An extra metal ridge may be cast around the area planned for the joint so that this metal can be hammered over the seam to disguise it after joining. The use of tangs and other types of extensions is common in many cultures.

1.2.4 Miscellaneous

-

A simpler way to attach a figure to a base is with screws inserted through holes drilled and tapped in the separately cast base, and then into tabs cast on the interior of the feet through which holes have also been drilled and tapped (fig. 220). See I.4§2.6 for more about nuts and bolts and how they may help to date a bronze.

-

Armatures that are preserved after casting may be used to attach sculptures to separate bases (fig. 221). And in the case of bronzes cast in parts, or damaged archaeological bronzes that need support, a structural armature may be fabricated to fit inside the bronze post-casting to hold the parts in place and anchor them to a base (fig. 222).

-

Metal tabs attached to one piece can be bent over the adjoining piece, usually on the interior. Examples on cast bronze sculpture are unknown to date. This technique is more usual on sculptures made of hammered sheet metal (fig. 223).

-

Dovetail joints, more commonly found in woodwork, have also been used to join separately cast elements (fig. 224). These too may be designed to slot easily together and come apart.

-

Cold-hammer joining, also known as pressure joining, consists of hammering two pieces of metal together with enough pressure to deform the metal until a joint is attained. It is difficult to achieve on copper alloys and lacks strength, as it does not produce a metallurgical joint. A rare example of this technique is found on solid-cast Chola dynasty (855–1280 CE) Indian bronzes (fig. 216).

-

A consecrated sculptural image may contain sacred relics that were deposited inside after casting. To close the aperture, sheet metal is generally mechanically joined and held in place using metal burrs around the opening (figs. 225, 226).

-

Organic adhesives such as waxes, bitumen, or resins may also be used to join components. Plaster, cement, and other such materials have also been used to hold sculptures together.

2 Why investigate assemblies? and other FAQs

As with other technical features, the location, pattern, and type of assembly can be informative regarding choices that were made at the time of the sculpture’s creation (the original structure potentially represented by a casting map), technologies available, and skill of the founder. They can also reveal information about flaws and damage—the structural integrity and condition of an object. Discovery of anachronistic technologies can lead to a reevaluation of the dating of a bronze or to the presence of restoration work.

2.1 Is it possible to distinguish between a metal-to-metal

joint and a wax-to-wax joint?

In some circumstances, both types of joints may look alike, particularly on radiography, where they may both exhibit circular or elliptical metal wall thickening. Here are some clues to make the distinction:

-

The exterior of wax joints can be smoothed relatively easily and is generally not visible on the outside of the subsequent cast. In contrast, separately cast sections that are then joined in the metal may have a gap that needs to be hidden with cold work. Strong lighting may reveal such metal-to-metal joints. Special attention is required for large bronzes from classical antiquity, where fusion welding was often carried out so perfectly as to be completely undetectable.10

-

Unlike wax joints, metal joints imply separately cast parts, and thus possible differences in the alloy composition of the different parts. Also, should they be present, brazing and soldering generate varying alloy compositions at the joint.

-

Wax joints present either a lack of metal or a small amount of extra metal on the inside of the joint. Fusion welding (including flow fusion welding) may generate extensive additional metal along the joint.11

2.2 Is it possible to distinguish between different

metallurgical joints (brazing, soldering, and flow fusion

welding)?

Brazing and soldering usually appear on the surface as straight lines (fig. 206), whereas flow fusion welds often look like chains of ovals (figs. 204, 227). However, these features may be hidden, and flow fusion welds have been known to appear as straight lines. Radiography and/or surface elemental analysis may prove necessary to distinguish between flow fusion welding and brazing on the one hand (copper alloy), and soldering on the other (denser metals such as lead or tin alloys). Whereas brazing necessarily uses a slightly lower-melting-point copper alloy than that of the sculpture (primary metal), a weld will use a circa identical melting-point alloy. However, surface elemental analysis may not be sufficient to distinguish fusion welding from brazing, since results may be highly affected by patina or corrosion, thus necessitating a very accurate and well-located sampling of sound metal, or a metallographic analysis (figs. 146, 228, 229). In many cases the location of the area of interest may prove difficult to access in order to take a sample.

2.3 Is it possible to distinguish between features

associated with the original assembly in the foundry and

joints linked to later repairs?

-

Elements such as tenons or sleeves cast with the bulk of the sculpture to accommodate the securing of a limb suggest that the figure was designed to be cast in parts.

-

Repairs undertaken at a later date are sometimes made of a significantly different alloy than the original. This usually shows up in the manner used to attach the repairs and through differences in color.

-

If significant time has elapsed, the difference in or lack of patina on the new repairs may help to identify them.

-

If the object dates to before the mid-nineteenth century, repairs attached using more modern methods such as machine-made screws and bolts will be identifiable as new.

-

It is often possible to distinguish modern solders by their composition, which might include elements that have only been available in recent times, but this requires analysis.

2.4 What can we learn by investigating the way in which a

sculpture is assembled? Can it indicate something about

the workshop or the period?

The very fact of a sculpture having been cast in sections may be specific to a period and therefore provide an initial indication of the date of production.12 The sequence and method by which a sculpture was assembled may be characteristic of a foundry, workshop, or period. It may reflect a founder’s ability to cast large pieces or indicate preferences for certain types of complex , idiosyncratic sprueing systems, and mastery of efficient joining processes. To date not enough studies have been carried out on related bronzes with documentation using casting plans to characterize a workshop or period. Adopting the practice of making a casting plan to document the separately cast elements of a sculpture could be helpful in comparing the joining methods used.

2.5 What can the assembly technique tell us about the

workshop or the period?

A number of assembly techniques such as sleeve joints are ubiquitous throughout human production of bronzes. However, some may be specific to a foundry or characteristic of a culture. For instance, flow fusion welding to date is only known to have been used broadly in the fabrication of bronzes during classical antiquity.13 Then, also, the aforementioned Chola dynasty bronzes made during the ninth to thirteenth centuries in south India show unique joining techniques (fig. 216). And in Renaissance Europe, the use of handmade screws were designed to add elements to Severo da Ravenna’s (Italian, active 1496–before 1538) bronzes.14 More studies are needed to draw firm conclusions for other contexts (for example modern Europe or Asia).

3 Checklist: How do we investigate and differentiate assembly features?

Detecting what assembly methods have been used can prove difficult because the evidence may have been obscured during the chasing and finishing or hidden by corrosion (the latter tends to reveal to the naked eye more than it hides, but prevents any accurate surface analysis). Pay particular attention to areas that might have been added as appendages, such as arms, hands, legs, heads, objects held in hands (including attributes), bases, elaborate drapery folds or coiffures, halos, or jewelry, as well as , variations in metal color, rivets, or plugs. For details in examination and analytical techniques please refer to tables 5, 10, 13 Open viewer.

3.1 Visual examination, including raking light, microscopy

Direct visual examination is usually the first step when looking for joints. These may be indicated by a variation in surface coloration, uneven surfaces, or thin gaps between sections, whatever the process. The aid of a binocular microscope and the use of raking light may be useful. As indicated above, the presence of screws, bolts, nails, staples, plugs, or pins may indicate a joint area.

3.2 Nondestructive testing, including radiography,

ultrasonic testing, eddy currents, thermography

Radiography (whatever the source: X-ray, gamma, neutrons) may help identify the presence and type of joint. Any additional metal that might have flowed around the joint on the interior is easily detected by radiography (figs. 187, 206), as are most mechanical joints (figs. 211, 212). An industrial CT scan may prove necessary to resolve specific joining queries.15

Ultrasonic testing may detect discontinuities in the metal surface that indicate the presence of joints. This type of testing is also sensitive to variations of metal thickness and density and is thus able to track metallurgical joints (figs. 230, 231).

By using eddy current measurements across a suspected joint, it might be possible to detect a change in variation in the electrical conductivity and magnetic permeability of an object that is not otherwise visible, thereby identifying a joint (but hardly the precise process of joining).

Thermography may also reveal a thermal anomaly at a joint and/or changes in thermal behavior between two separately cast parts.

3.3 Analytical techniques without sampling

Surface elemental analysis such as X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) or particle-induced X-ray emission spectroscopy (PIXE) can detect differences in the alloy composition when scanned across a suspected joint (see fig. 188 and II.6§2.2 for details and limitations). It can help distinguish a metallurgical joint (variations in alloy composition) from a mechanical joint (no added metal, and therefore no variations in alloy). It can also reveal the presence of solder (a non-copper alloy).

3.4 Analytical techniques requiring sampling

Sampling is generally only carried out when nondestructive methods have failed to produce clear results (see II.5§4, II.6§3). In order to identify slight variations in metal composition (for example from separately cast parts, later additions, or repairs) it may be necessary to drill metal samples for analysis using high-sensitivity techniques. Metallographic cross sections may be necessary to distinguish between flow fusion welding and brazing by revealing the different microstructures (figs. 228, 229) Although an unusual step to take, cross sections may also reveal cast-on joints (fig. 209).

Notes

-

Separate casting may be part of serial production systems, as seen in a number of cultures, including the Khmer Angkorian period (Bourgarit, David, Benoît Mille, Thierry Borel, Pierre Baptiste, and Thierry Zéphir. 2003. “A Millennium of Khmer Bronze Metallurgy.” In Scientific Research in the Field of Asian Art: Proceedings of the First Forbes Symposium at the Freer Gallery of Art, edited by Paul Jett, 103–26. London: Archetype.) and nineteenth-century bronze in France (Lebon, Elisabeth. 2003. Dictionnaire des fondeurs de bronze d’art. France 1890–1950. Perth, Australia: Marjon éditions., 45). It can also be used to allow iconographic flexibility, as seen for example with Roman imperial statuettes (Hill, Dorothy K. 1982. “Note on the Piecing of Bronze Statuettes.” Hesperia 51 (3): 277–83., kindly advised by S. Descamps) and in sculptures by Hubert Le Sueur (French, ca. 1580–1658) and contemporaries, whose small equestrian sculptures had interchangeable heads (see for example Leithe-Jasper, Manfred. 1986. Renaissance Master Bronzes from the Collection of the Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna. Washington, DC: Scala Books., 246–53, cat. nos. 66a and b [Manfred Leithe-Jasper]; Evelyn, Peta. 2000. “The Equestrian Bronzes of Hubert le Sueur.” In Giambologna tra Firenze e l’Europa. Atti del Convegno Internazionale, Firenze, Istituto universitario olandese di storia dell’arte, 1995, edited by Sabine Eiche, 141–56. Florence: Centro Di., 144–45). ↩︎

-

Haynes, Denys Eyre Lankester. 1992. The Technique of Greek Bronze Statuary. Mainz, Germany: Philipp von Zabern., 95; Descamps-Lequime, Sophie, and Benoît Mille. 2017. “Progrès de la recherche sur la statuaire antique en bronze.” Technè 45:4–13.. ↩︎

-

For instance, the Sienese metallurgist Vannoccio Biringuccio (Italian, 1480–before 1539) describes such a process for repairing cracks in bells (Biringuccio, Vannoccio. (1540) 1990. The Pirotechnia of Vannoccio Biringuccio. Translated by Cyril Stanley Smith and Martha Teach Gnudi. New York: American Institute of Mining and Metallurgical Engineers., book VI, ch. 15, 275–77). ↩︎

-

Carlisle, Rodney. 2005. Scientific American Inventions and Discoveries: All the Milestones in Ingenuity, from the Discovery of Fire to the Invention of the Microwave Oven. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley., 365. ↩︎

-

Formigli, Edilberto. 1984. “Due bronzi da Riace.” Bolletino d’Arte 2, special series 3. Rome: Libreria dello Stato. http://www.bollettinodarte.beniculturali.it/opencms/multimedia/BollettinoArteIt/documents/1475238151057_Due_Bronzi_di_Riace_I_(Serie_speciale_1984).pdf.; Descamps-Lequime, Sophie, and Benoît Mille. 2017. “Progrès de la recherche sur la statuaire antique en bronze.” Technè 45:4–13.. ↩︎

-

Massimiliano Soldani Benzi (Italian, 1656–1740) describes in a letter to his London agent that in making bronzes, solder is never used to join separate pieces together, but only molten bronze of the same alloy so that the color will be identical. Unpublished document, referred to in a 1996 conference paper by Dr. Charles Avery in Berlin. We are grateful to Dr. Avery for allowing us to include his discovery prior to publication. ↩︎

-

Gettens, Rutherford J. 1967. “Joining Methods in the Fabrication of Ancient Chinese Bronze Ceremonial Vessels.” In Application of Science in Examination of Works of Art; Proceedings of the Seminar: September 7-16, 1965, 205–17. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.. ↩︎

-

One example is Leone Leoni’s (Italian, 1509–1590) fabulous sculpture of Charles V and the Fury (1551–55) in the Museo del Prado, Madrid, whose armor can be taken off, revealing the nude king. ↩︎

-

See Suverkrop, E. A. 1912. “The Molding of Bronze Statuary.” American Machinist 37 (23): 923–28., 928. ↩︎

-

See for example the Piombino Apollo (Greek, 120–100 BC, H: 115.5 cm, Musée du Louvre, inv. Br2). The weld joint between the legs and the body is so perfect that despite thorough examination (X-radiography, endoscopy, phased-array ultrasonic testing), it was only revealed at one small area, namely a platform joint between the two legs. Based on this observation, either each leg was cast separately, or one or the other leg was cast separately and joined to the body (Mille, Benoît, and Sophie Descamps-Lequime. 2017. “A Technological Reexamination of the Piombino Apollo.” In Artistry in Bronze: The Greeks and Their Legacy: XIXth International Congress on Ancient Bronzes, edited by Jens M. Daehner, Kenneth Lapatin, and Ambra Spinelli, 349–60. Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum and Getty Conservation Institute. http://www.getty.edu/publications/artistryinbronze/conservation-and-analysis/42-mille-descamps/., figs. 42.5, 42.7). ↩︎

-

For example, traditional X-radiography showed the presence of an increased flow of metal on the interior of the neck area of a thirteenth-century Khmer sculpture depicting Seated Brahma, now in the collection of the Walters Art Museum, Baltimore (inv. 54.2734, H. 29.5 cm). This could be interpreted as the thickening that occurs in a wax casting model when a separately cast head is attached to the body using a wax-to-wax joint. However, examination of sequential images in a CT scan showing the neck in profile and face-on revealed a thickness of metal across the interior of the neck and extensive metal flow along the armature extending into the body, implying a cast-on technique was used to cast the head onto an already-cast body (fig. 232). This was then verified via an X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy (XRF) scan across the joint (Lauffenburger, J., D. Strahan, and G. Gates. 2016. “Two Bàyon-Period Khmer Bronzes in the Walters Art Museum: Technical Study Revisited.” In Metal 2016, Proceedings of the Interim Meeting of the ICOM-CC Metals Working Group, September 26–30, 2016, New Delhi, India, edited by R. Menon, C. Chemello, and A. Pandya, 30–39. Paris: ICOM-CC & Indira Gandhi National Centre of the Arts., 33). ↩︎

-

For example, all ancient large bronzes studied to date have been shown to be cast in sections and assembled (Mille, Benoît. 2017. “D’une amulette en cuivre aux grandes statues de bronze, évolution des techniques de fonte à la cire perdue, de l’Indus à la Méditerranée, du 5e millénaire au 5e siècle av. J.-C.” PhD diss., Université de Paris-Nanterre et Université de Fribourg. http://www.theses.fr/2017PA100057.). Early Italian Renaissance large bronzes were also cast in sections, but a number of Renaissance bronzes from Italy and France were cast in one pour, without any assembly; see for example Bourgarit, David, Jane Bassett, Francesca G. Bewer, Geneviève Bresc-Bautier, Philippe Malgouyres, and Guilhem Scherf, eds. 2014. French Bronze Sculpture: Materials and Techniques 16th–18th Century. Paris: Archetype.. For a summary of attitudes toward the single pour see Motture, Peta. 2019. The Culture of Bronze: Making and Meaning in Italian Renaissance Sculpture. London: V&A Publishing., 227–28, with references. See Case Study 7§4 for the way Andrew Lacey, a contemporary artist and founder, envisions his casting plans. ↩︎

-

Descamps-Lequime, Sophie, and Benoît Mille. 2017. “Progrès de la recherche sur la statuaire antique en bronze.” Technè 45:4–13.. In addition, a typology has been set up for the oval-shape variant (welding in basins) of flow fusion welding (Azéma, Aurélia. 2013. “Les techniques de soudage de la grande statuaire antique en bronze: etude des paramètres thermiques et chimiques contrôlant le soudage par fusion au bronze liquide.” PhD diss., Pierre et Marie-Curie, Paris VI. https://tel.archives-ouvertes.fr/tel-00918829., 140; Azéma, Aurélia, Daniel Chauveau, Gaëlle Porot, Florent Angelini, and Benoît Mille. 2017. “Pour une meilleure compréhension du procédé de soudage de la grande statuaire antique en bronze: Analyses et modélisation expérimentale.” Techné 45:73–83.). The distinguishing features include the way the sections to be welded are prepared, and whether the welding is superficial or goes through the entire thickness of the metal wall. It is not yet clear if these variants have a chronological significance. Hopefully, this typological approach will be extended to objects from other periods and/or geographical areas, for example Asian bronzes. ↩︎

-

Stone, Richard E. 2006. “Severo Calzetta da Ravenna and the Indirectly Cast Bronze.” Burlington Magazine 148:810–19.; Smith, Dylan. 2008b. “I bronzi di Severo da Ravenna: Un approcio tecnologico per la cronologia.” In L’Industria artistica del bronzo del rinascimento a Venezia e nell’Italia settentrionale: Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi; Venezia, Fondazione Giorgio Cini, 23 e 24 Ottobre 2007, edited by Matteo Ceriana, 49–80. Verona, Italy: Scripta.; Smith, Dylan. 2013. “Reconstructing the Casting Technique of Severo da Ravenna’s Neptune.” Facture 1:167–81.; Warren, Jeremy, 2014. Medieval and Renaissance Sculpture: A Catalogue of the Collection in the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, Vol. I. Sculptures in Metal. Oxford: Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford., 140–41. ↩︎

-

Formigli, Edilberto. 1984. “Due bronzi da Riace.” Bolletino d’Arte 2, special series 3. Rome: Libreria dello Stato. http://www.bollettinodarte.beniculturali.it/opencms/multimedia/BollettinoArteIt/documents/1475238151057_Due_Bronzi_di_Riace_I_(Serie_speciale_1984).pdf.; Descamps-Lequime, Sophie, and Benoît Mille. 2017. “Progrès de la recherche sur la statuaire antique en bronze.” Technè 45:4–13.. ↩︎